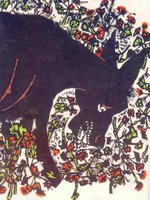

“Platero es pequeño, peludo, suave; tan blando por fuera, que se diría todo de algodón, que no lleva huesos. Sólo los espejos de azabache de sus ojos son duros cual dos escarabajos de cristal negro.

“Platero es pequeño, peludo, suave; tan blando por fuera, que se diría todo de algodón, que no lleva huesos. Sólo los espejos de azabache de sus ojos son duros cual dos escarabajos de cristal negro.

Lo dejo suelto, y se va al prado, y acaricia tibiamente con su hocico, rozándolas apenas, las florecillas rosas, celestes y gualdas… Lo llamo dulcemente: «Platero?», y viene a mí con un trotecillo alegre que parece que se ríe, en no sé qué cascabeleo ideal…

Come cuanto le doy. Le gustan las naranjas, mandarinas, las uvas moscateles, todas de ámbar, los higos morados, con su cristalina gotita de miel…

Es tierno y mimoso igual que un niño, que una niña…; pero fuerte y seco por dentro, como de piedra. Cuando paso sobre él, los domingos, por las últimas callejas del pueblo, los hombres del campo, vestidos de limpio y despaciosos, se quedan mirándolo:

–Tien’ asero…

Tiene acero. Acero y plata de luna, al mismo tiempo.” – Juan Ramón Jiménez

Most of this I typed from memory, some 15 years after having to recite it as part of a college course. One of my final classes as a Spanish major was a course in Spanish phonetics and phonology. Very difficult and scary course. I was one of only a handful of *Anglo* Spanish majors at my college; I always thought this to be a good thing because school was the only place for me to practice Spanish and I was able to practice with and learn from native speakers of the language, rather than other *gringos* like myself.

In addition to learning the phonetic alphabet (which is like a whole other language) a large part of the coursework was recitation of poetry and prose. We used many of the literary works that I had been forced to analize bit by bit in my literature courses. Only now I had to tear them apart bit by bit, re-writing each phonetically and reciting them over and over to get the pronunciation of every sound just right. Each of us had to stand in front of the class and recite. At any slight mispronunciation my professor made us start over at the beginning. Over and over we did this, day after day. Some of it was awful, tricky stuff (akin to Shakespeare), but others, like this piece, were great fun and almost a joy to recite. I dreaded taking my turn in front of the class each day and chuckled quietly to myself at the mistakes made by the native speakers. It might sound mean-spirited, but it gave me a lot of confidence to realize that their pronunciation wasn’t perfect either! This course did wonders for my accent and I’d always wished that I’d been introduced to the techniques sooner. When I was teaching high-school Spanish, I sometimes made my students do recitation, which they *enjoyed* about as much as I did. I’m sure they hated me for it, but it was good for them… and maybe they learned to love the story of Platero the donkey the way that I once loved it.

“Platero is so little, so hairy, smooth, and so soft to the touch that you might say he is made of puffy cotton, all light and boneless. Only do the mirrors of his dark eyes seem to be hard, jet-black, like two beetles, like two scarabs made of brilliant glass.

I turn him loose and he goes off straight to the meadow, fondling, caressing the blossoms, his muzzle barely brushing the tender flowers, sky-blue as the air, golden as the sun, pink and red as the sunrise and sunset… Then softly I call to him, “Platero?” and he comes to me with a happy trot, running with such a merry jingle that it seems to me like a vague tinkling, a laughter he makes…

What I give him he eats. He loves the taste of amber-colored muscatel grapes, mandarin oranges, and the deep purple figs as they burst with their crystalline honey, a sweetness of warm, golden drops…

He is tender and finicky like a young boy, a small girl, a child… but inside he is strong, he is dry like rock, like the land he walks. When I ride him on Sundays through the outskirts of the small village, down the streets, the narrow lanes, field men, the strong men, all dressed in their Sunday clothes, stand and look; slowly they watch and speak of him:

“Steel, he’s got steel…”

Yes, he’s got steel. Steel and the silvery sheen of the moonlight, and all at the same time.” – translation by Myra Cohn Livingston and Joseph F. Dominguez